Spring Salamander

As an elephant biologist my work usually revolves around looking for movement in the canopy, hearing the twigs break and scanning massive footprints. In North America where so few large predators remain and bears are yet to wake up from their slumber and birds yet to migrate back, I found myself with a bunch of researchers and students from 10 different Universities in the US at the Great Smoky Mountain National Park.

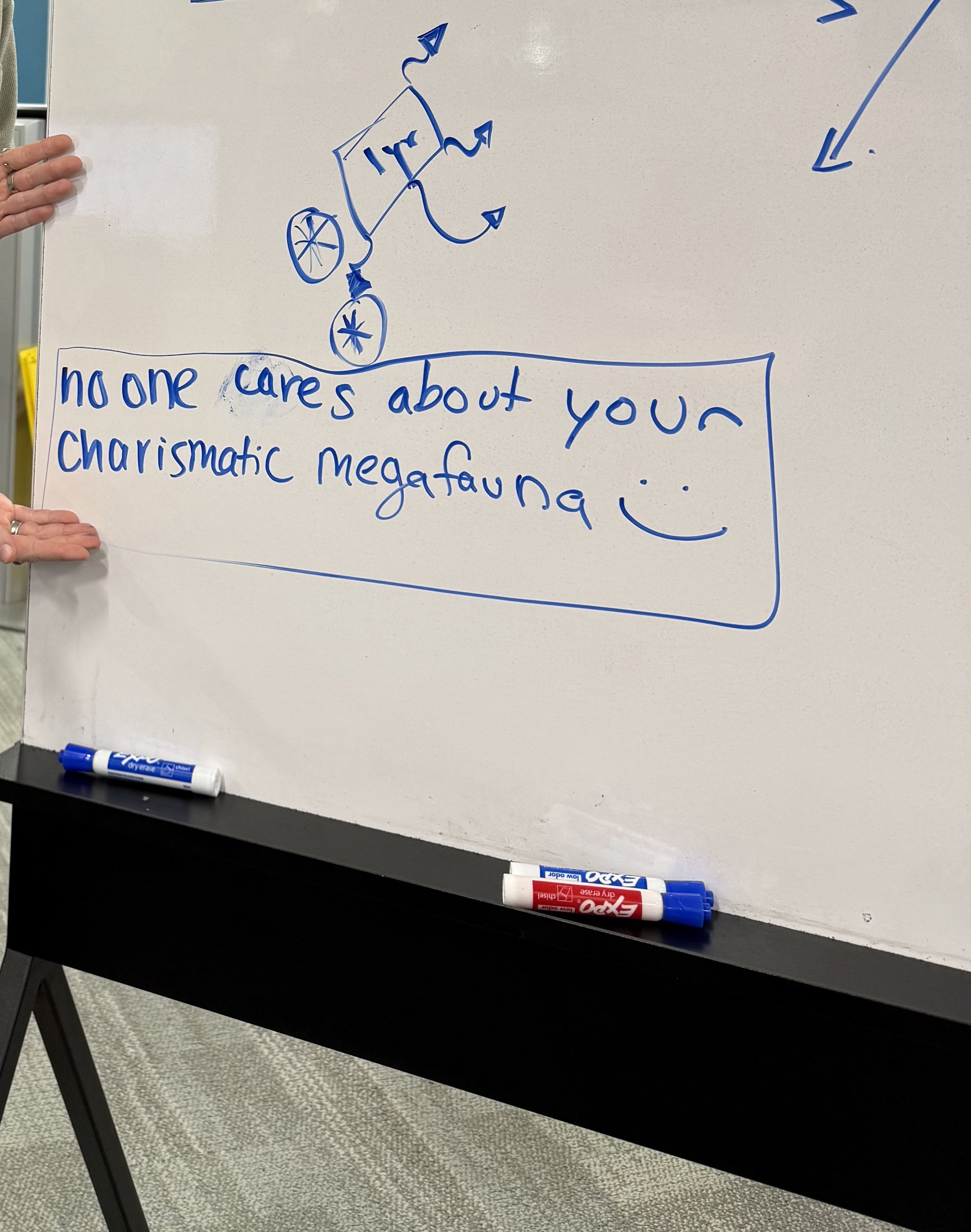

At first my eyes, trained to spot elephant signs, failed to detect any movement beneath slick, moss-covered stones. I waded through frigid streams and lifted each slab with cautious effort, but soon set the task aside in boredom. Then I recalled my ecologist best friend’s smug challenge to my skills—he’d accused me of a mega-fauna bias and ignorance toward anything small, a charge I couldn’t have denied before this day.

When it was time to go back, I decided to use my elephant-tracking skills to search for salamanders. My motto has been to think like the animal I am looking for. In this case, I knew too little about salamanders to think like one and wasn’t even sure if they could think (Ryczko, 2020). So I thought like a frog. I had almost failed a practical exam at the Wildlife Institute because I refused to catch a toad and put a glow bulb in its mouth; also, it was terribly cold for frogs, or at least I thought it was. But then I heard the researcher accompanying us instruct us to look for dark, moist places. Watching undergrads catch their first dusky and striped salamanders, I felt the pressure to catch one too. My advisor had handled a dusky salamander and handed it to me the day before, and I actually thought it would be nice to catch one myself.

I resumed my search, and this time I was more determined. I went to the largest boulder I could find and toppled it, only to see sunlight falling on a bright orange creature resting peacefully in gently flowing water among a layer of moss and decomposing litter. It was one of the most beautiful surprises I have ever experienced in my wildlife career. I was reminded of the time I was attacked by a trinket snake in Tadoba National Park while doing camera trapping, but even that did not compare to this jewel of the Smokies. I called a friend to bring a ziplock bag and a cone so we could return it to its exact spot after taking measurements. Although we’d been cautioned not to handle salamanders if we’d applied lotion— which I never —I picked it up and held it in my hand. It felt even more delicate than a frog. Its tiny legs were adorable, and I wondered if they left footprints. Its body was covered in spots like those of a miniature leopard; the pattern, color, and eyes mesmerized me. Later, the lead researcher told me it was one of the largest spring salamanders recorded in that landscape. I snapped a few pictures and recorded a video to send to my ecologist friend, who could not have dreamed of catching one that big. When I released it, I felt humbled by the experience, was reminded to appreciate the small things in nature and correct my mega-fauna bias.

Interestingly, another friend accused me of Megafauna bias a month later. I purchased a field guide for reptiles of North Carolina that lies on my desk.

References:

Ryczko D et al. (2020). “Walking with salamanders: From molecules to biorobotics.” Trends in Neurosciences, 43(5):323–336. This review discusses calcium-imaging recordings from reticulospinal neurons in the isolated salamander brain and their role in generating locomotor rhythms

Spring Salamander - aka - king of salamanders

The spring salamander (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) is a large, slender-bodied amphibian native to cool, fast‑flowing springs and streams in eastern North America.

It typically reaches 15–23 cm in length, boasting a pinkish to reddish hue speckled with faint spots and a broad, flattened head.

A nocturnal predator, it not only consumes insects and aquatic invertebrates but is also notorious for preying on other salamanders, including smaller larvae and species.